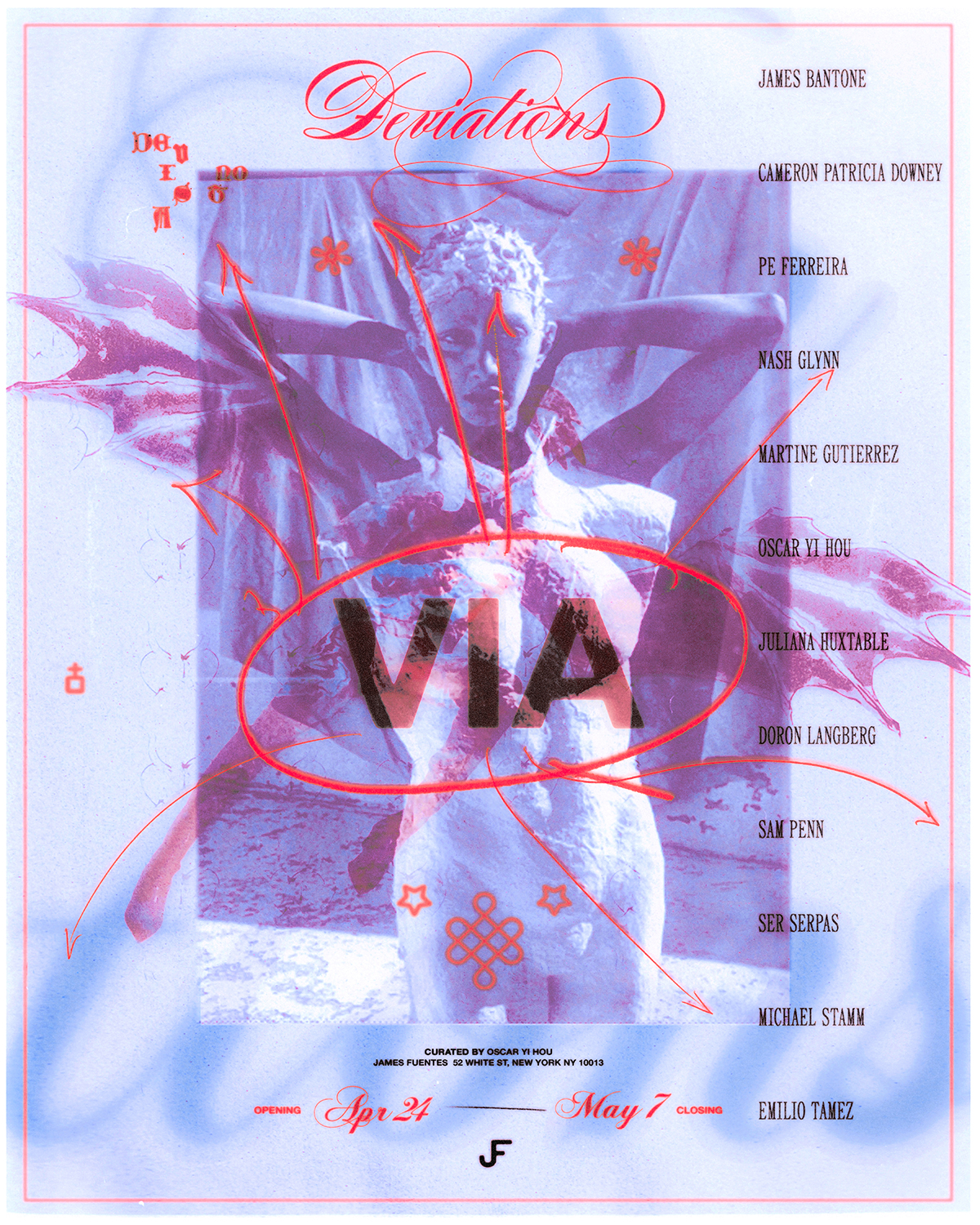

DEVIATIONS

CAMERON PATRICIA DOWNEY, DORON LANGBERG, EMILIO TAMEZ, JAMES BANTONE, JULIANA HUXTABLE, NASH GLYNN, MARTINE GUTIERREZ, MICHAEL STAMM, OSCAR YI HOU, PE FERREIRA, SAM PENN, SER SERPAS

Curated by Oscar yi Hou

April 24–May 7, 2025

CAMERON PATRICIA DOWNEY, DORON LANGBERG, EMILIO TAMEZ, JAMES BANTONE, JULIANA HUXTABLE, NASH GLYNN, MARTINE GUTIERREZ, MICHAEL STAMM, OSCAR YI HOU, PE FERREIRA, SAM PENN, SER SERPAS

Curated by Oscar yi Hou

April 24–May 7, 2025

Opening reception:

Thursday, April 24, 6-8pm

52 White St

New York, NY 10013

(212) 577-1201

info@jamesfuentes.com

PR by Max Battle

Flyer by Daniel Leyva

Thursday, April 24, 6-8pm

52 White St

New York, NY 10013

(212) 577-1201

info@jamesfuentes.com

PR by Max Battle

Flyer by Daniel Leyva

Text by hannah baer

DEVIATIONS is a group show of 12 artists, most of whom I know more or less intimately, and most of whom are trans or gay and/or hang out “downtown” (a word which here alludes to but does not in fact denote geography). The works are almost all either portraits or sculptures, some self-portraits and in more than one case, a portrayal of another artist in the show. In this way the works form a web of sociality that supersedes but also links to physical space, much like the non-geographic downtown which the artists represent. You may not personally know these artists, but to know that they largely know each other is perhaps to understand some aspect of how they arrived together here.

Some people who study the mind believe one’s unconscious is populated by so-called “objects”; for example, a maternal object describes a shape into which you fit people who remind you of your mother (which is also a word used to describe someone who raised you in the scene). To portray someone is also, concretely, to make their likeness into a physical object. To place such portraits alongside sculptures—or a painting of a sculpture (Michael Stamm), a photograph of a figure with an object (Pe Ferreira), or of the artist herself with a sculpture as clothing (Martine Gutierrez)—suggests the friction between the person and/as the object, especially in a socio-visual culture that centers visibility and glamor. The totality of objects in your unconscious, and the relation between them, is said to constitute your “object world.”

These works in relief of one another instantiate visceral questions about the nature of subjectivity in relation to the plausible object in one’s mind (a recognizable chair) versus the object in the world, perhaps distorted (a chair with elongated legs, Cameron Patricia Downey). When you look at an object, does it look back at you? (Sam Penn’s two chiaroscuric portraits suggest that a moment of not-looking may still constitute acknowledgement.) Such riddles abound, as do themes around contact, reification and its disruption, and ekphrasis, or the depiction of one work within another.

Or, I would put it another way, and did, in fact, first write about these pieces in language that hews more closely to form, to the object, ekphrastic too but not only, in what follows:

the friction between

the world as it is and the world as it we hold it in mind

your body knocking into

your own furniture (that you

acquired in a hope that it would

make people like or respect you

though it is hard to admit)

in the dark

and/also

tracing the curve

of a friend

’s cheek or hip

(a friend you pursued because

being near her left a residue)

again, obviously,

in the dark

(or doron whispering something to me

on the dancefloor about how he felt in his

body when painting someone

else’s body)

(that one might feel studying her own body)

relaxing into

the friction (pressure?)

between your friend as she is and

your friend as you hold her in mind, deviations

between one and the other notwithstanding

–can i ask about a so-called term of art: ekphrastic

thing-within-thing

you looking at someone you admire and then she’s in you

relating as rendering, reproducing, making concrete

the world as it is and the world as it we hold it in mind

your body knocking into

your own furniture (that you

acquired in a hope that it would

make people like or respect you

though it is hard to admit)

in the dark

and/also

tracing the curve

of a friend

’s cheek or hip

(a friend you pursued because

being near her left a residue)

again, obviously,

in the dark

(or doron whispering something to me

on the dancefloor about how he felt in his

body when painting someone

else’s body)

(that one might feel studying her own body)

relaxing into

the friction (pressure?)

between your friend as she is and

your friend as you hold her in mind, deviations

between one and the other notwithstanding

–can i ask about a so-called term of art: ekphrastic

thing-within-thing

you looking at someone you admire and then she’s in you

relating as rendering, reproducing, making concrete

“once removed,” like a cousin, like trade who never leaves

friction magnified by exquisite attention

or another term of art to refer to the person in the mind: “object”

as in, “object world”

the acquisitive impulse here, wanting to take someone in, wanting to render them

something taut between what’s imagined and what you touch

that heaves and sometimes collapses with contact

(harris said “correspondences”) which is accurate, or

who you are in my mind is part of a web between all our bodies

mediated not as much by possessions, not as much by like and dislike

but the network of friction, pressure, and groping

a generation of young people who talk to each other, represent each other, follow each other into caves and back rooms

and so, in our minds, in our choreography, in our renderings of one another, correspond.

friction magnified by exquisite attention

or another term of art to refer to the person in the mind: “object”

as in, “object world”

the acquisitive impulse here, wanting to take someone in, wanting to render them

something taut between what’s imagined and what you touch

that heaves and sometimes collapses with contact

(harris said “correspondences”) which is accurate, or

who you are in my mind is part of a web between all our bodies

mediated not as much by possessions, not as much by like and dislike

but the network of friction, pressure, and groping

a generation of young people who talk to each other, represent each other, follow each other into caves and back rooms

and so, in our minds, in our choreography, in our renderings of one another, correspond.

Curatorial Statement

Oscar yi Hou

I began this friends-and-family exhibition somewhat last minute, with no aspirational grand narrative or through-line. But quickly, some threads became apparent. And to be clear, I did not intend for the show to comprise artists of any specific identity, save for artist—the queerness of it all is more a reflection of my lifeworld than it is of anything else. DEVIATIONS, alongside this text, is an attempt to describe, not prescribe, what already exists in the world.

When I’m feeling playful with my semantics, I like to differentiate between a piece of art (an art-object) and an art work. As a kind of gerund, the artwork is the phenomenon by which an art-object does meaningful work onto you. It exerts a force onto the viewer, which moves some part of them.

Bodywork might describe artwork that does work onto the body. Not the viewer’s personal body per se, but rather the discursive formation of the body. In other words, what is conjured in the state’s imaginary by the word body. Through apparatuses like legislature, textbooks, or medicine, the state proscribes what bodies are to exist within the state’s own, well… body.

The state delimits what is a normative body. And it’s through this disciplining that we encounter the deviant body—those forms of people rendered extrinsic to the contours of the state. Bodywork destabilizes the normative body. It works it; resignifies it. It declares its own freedom (to deviate). When we say that one’s body is tea, it implies that the body can constitute its own drama, worthy of awe and gossip, soft gasps. Enough of a deviation to rework the very notion of what a body is and what it could be.

I find that queer art practices often concern themselves with the body, as the body is the interface onto which deviancy is first inscribed. Perhaps medically, at birth… then through ornamentation, aesthetics; an errant earring, jeans fitting too tight. Or too loose. The wrong hairstyle. However deviance finds itself most clockable in its performance, its doing. The sway of a hip, the slack of a wrist. The wrong smile for the wrong person.

Indeed, in light of the ways in which queers perform their bodies—may it be penetrating the other’s body in purportedly exotic ways, medically alchemizing their bodies, or chemical interventions for the basest need of all: the pleasure principle—do we see how bodywork is rendered an unavoidably queer phenomenon.

For an artwork to do bodywork, it does not need to represent a body literally. A figure is the form of a body, yes; but the form of a body can also be its absence, remnant, or impression. A shadow can be a figure, but not a body, for example.

In DEVIATIONS, the works by Cameron, Ser, and Michael contain the absent-presence of bodies. A seat for a body. An installation with objects that bodies have done work to, moved through, then discarded. Or the allusion to a body as recipient of chemical pleasure. These works do work onto the body through their retooling of objects and/or chemicals. The motion, leisure, and pleasure of a body are all implied through its absence.

Several works depict others, or the artists themselves. My painting is of Emilio, for example. Doron’s painting is of Nash; and Nash, Martine, and Juliana have all depicted themselves. (Sam has depicted Max, who has been helping behind the scenes with the show.) At large, DEVIATIONS figures a “web of sociality” (as hannah says) for the viewer. Beauty, gender, and personhood can all be pried into with these portraits.

But perhaps such topics are subsumed by a far more simple and elegant truth: that these works express life. Life as it is, as it could be, as it might as well be, for us.