Crane Seeking Comforts (Rome, April-May 2021)

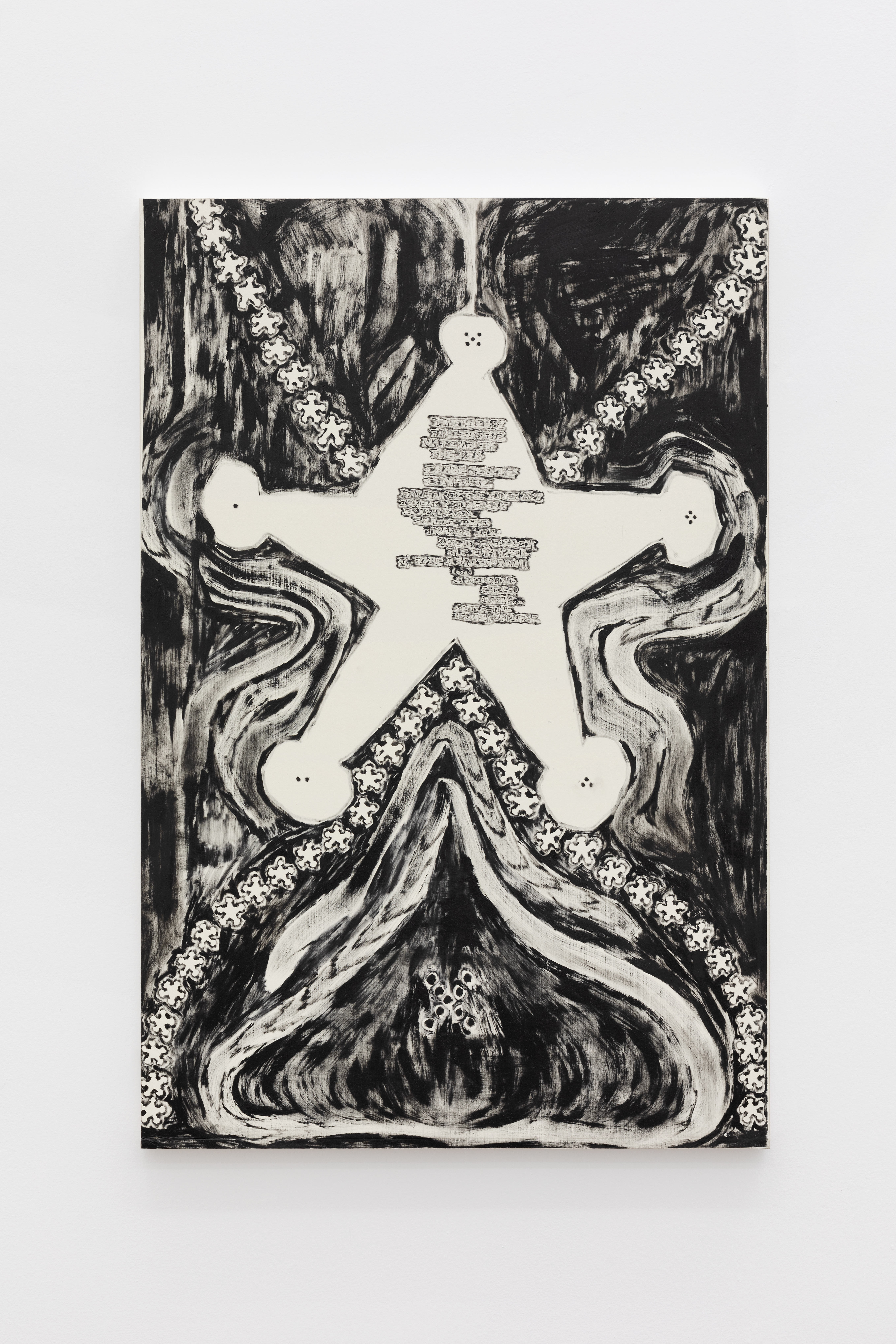

| Crane Seeking Comforts 9 April - 11 May, 2021 T293 is pleased to present Crane Seeking Comforts, Oscar yi Hou’s first solo exhibition in Italy. Eight mid-sized oil paintings on off-white paper will be on display. The symbolist painting practice of Oscar yi Hou (b. 1998) hybridises Western and Eastern iconography. Born and raised in Liverpool, England, to Cantonese immigrants, yi Hou’s work is influenced heavily by his diasporic upbringing. Through his artworks the artist plays with the estrangement of his ‘foreign’ origin— the mythical Orient — establishing a declaration of ‘otherness.’ The vertical format of this series of works, reminiscent of hanging scrolls, alongside his technical use of black dry-brush, indexes his deep interest in East Asian iconography. At the same time, he is equally captivated by North-American symbols such as the sheriff-star, cowboy hats, and the urban graffiti of New York City. By harmoniously combining these two visual and cultural worlds, yi Hou conjures a seductive autobiographical visual dialogue between the East and the West. Crane Seeking Comforts counts on a complex mythology of iconography and symbolism. yi Hou’s given Chinese name refers to an idiom that involves a bird— as such, the birds that appear throughout his practise are personifications of the artist himself. In IMUUR2, aka: Cowboy Crane, he represents himself in the margins as red-crowned cranes, traditionally auspicious birds in the Far East. In other works such as Twobird, aka: Copulation or Taijitu, aka: Cruising, pigeons are metonymically used to address and embody a queer narrative. In other works, such as Sphincter, aka: Two-Pines or Moonmad, aka: Cranekiss poems written by the artist himself are transformed into highly symbolic, quasi-mythological compositions. For these poem-pictures, yi Hou remixes the classical Chinese calligraphic poem form with his use of English script, interspersed with his trademark symbols of sheriff stars and Buddhist beads. His treatment of signs and language draws inspiration from the poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant’s text the ‘Poetics of Relation.’ The well-known ‘theory of Opacity’ by the Martinican writer, which embraces the unintelligibility and impenetrability of cross-cultural communication and consequently refuting complete knowability as a desirable goal, is one of the fils-rouges of yi Hou’s thinking. We can see this in the way he approaches the hegemony of English, treating it as if it were Chinese calligraphy. Yi Hou hides and buries his poems, rendering his native English as ‘inscrutable’ as Chinese may be to the West—and even to himself, by way of his own estranged relationship to the language. In submerging his text almost hieroglyphically, he kindly solicits from the viewers greater attention and patience, as he assures that the poems will slowly reveal themselves to a viewer should they sit with the intricate intimacies of the text a little longer. In his practice, Oscar yi Hou evokes the ancient Chinese tradition of the “Three Perfections,” classically used to mark the merging of a poet, a painter, and a calligrapher in a single artwork. By mixing language both as subject and object matter while also depicting expressive representations of his lived world as a queer man, Crane Seeking Comforts presents a nuanced insight into the postmodern diasporic condition of the 21st century. (Press release courtesy of T293 Gallery) |

April, 2021

Hi Oscar, tell us about Crane seeking comforts. How was the theme of the exhibition conceived?

Hello! There are a few themes in Crane Seeking Comforts, each conceived in a different way. The narrative theme came about from ruptures in my personal life, the dissolution of a long-term relationship. The title, “Crane Seeking Comforts”, is meant to harken to the gay personal/classified ads one would find in newspapers back in the day before the internet, listings that were often as pithy as they were heartfelt-- something like “Older Lonely Man Looking for that Special Someone. Lives in Manhattan. Can’t host.”

The titular ‘crane’ is metonymical for myself, as I outline in the self-portrait “IMUUR2, aka: Cowboy Crane”-- and so “Crane Seeking Comforts” refers to my own attempts to re-find intimacy, affection, and company. The other birds in the show— namely the pigeons— are also characterisations/and or metaphors for this act of ‘seeking comfort.’ The poem-picture works depict poems that I wrote that often similarly use the figure of the bird as metaphor to explore themes of relation and intimacy, especially through notions of flight/falling.

So I think the show is largely autobiographical, coming about from my own life-- albeit hidden under a layer of symbols, or hidden via my burying of the text. It’s a sort of layer of protection, to prevent over-exposure of the vulnerabilities in my own life.

Could you explain the significance of the symbols you used in the works: how did you choose them and how did they inspire you?

I try and encode a lot of meaning into my works through using symbols that I repeat and reiterate throughout my practice, so one of my intentions with Crane Seeking Comforts was to sort of outline the symbolic mythology I like to use—which symbol means what, for example. So, like I mentioned before, the self-portrait “IMUUR2, aka: Cowboy Crane” describes how the symbol of the crane throughout my practice is a signifier for myself. I picked the crane over other birds because they’re a very auspicious symbol in East Asian cultures.

I like to use the symbol of the five-pointed star because it’s such a crazy, fraught, multivalent symbol. It’s a symbol of nationalism in many cases—take the stars of the United States flag for example—but if you change the colour to red, it becomes the star of Socialism, which is of course deemed antithetical to America. Another symbol I like to is the Buddhist prayer bracelet, or mala-- as a kid, whenever I would go to China my family would buy them for me, and thus it signifies that personal history for me. In Sphincter, aka: Two-Pines, I hint at the sphincteral quality of the prayer beads—as such they also have a particular erotic signification.

When I fuse the five-pointed star with the prayer bracelet, I end up with the sheriff’s star, a star with circles on the end of each point —a symbol of power, policing, but also one that conjures up the Old Wild West of America. My use of cowboy iconography also speaks to my interest in this American mythic West. I like to juxtapose these signifiers of the old American Wild West alongside signifiers of the ‘Orient’ because the myth of the American West—of self-reliance, independence, Manifest Destiny—often elides the presence of Chinese labourers in America at the time in the mid-late 1800’s. These coolie labourers laid the tracks for the Transcontinential Railroad which was integral for westward expansion, but were erased from history, because their labour ran contrary to the mythic individualistic masculine self-reliant All-American man. America has a long history of anti-Chinese sentiment, including several laws that specifically banned Chinese people, because we were seen as diseased, too foreign, too alien, amongst other things. And of course we see its continuation today, with the rise of hate-crimes this past year against Asian-Americans. It’s all painfully ironic because the United States is where it is today in part because of the labour of those persecuted Chinese labourers during westward expansion.

So I like to think there’s a certain calculus to my symbology. Other symbols include Taijitu, aka: Cruising. ‘Taijitu’ refers to a symbol of Taoism, recognizably the ying-yang symbol, which is why I have the white and black bird circle each other.

Édouard Glissant ‘s Theory of Opacity has strongly inspired your works. Could you tell us how did you express this concept and how this theory has influenced your artistic production?

I like Glissant’s writing on identity, particularly its relational/rhizomatic aspect. His concept of ‘creolization’ is also really pertinent to my own practice of cultural hybridity, being caught between East and West, so to speak. Glissant claims that everyone should have the right to opacity, which is not the same to close one off completely, but instead, as I read it, to let others rest in their specificity and illegibility, rather than to try and fully ‘know’ them or to ‘translate’ them into something consumable.

I think about this in relation to the filmmaker/thinker Trinh T. Minh-ha, in this case specifically her text Woman Native Other. There’s this part where she writes how about ‘clear’ expression is often conflated with ‘correct’ expression, and the imposition of ‘clarity’ is applied onto rhetoric that is designed to persuade others—so thinking about clear commands, imperative sentences—authority, at base. She contrasts this with texts like the Tao Te Ching, which is a fundamental text of Taoism, or the language of Zen Buddhism. They’re both examples of rhetoric that is often seen as cryptic, paradoxical, and mysterious, but ultimately accessible and conducive to greater understanding. Rather than didactically imposing a message onto the reader, they instead invite the reader in, to parse through the language with greater care, concern, and ultimately understanding.

I also this in relation to Rey Chow, an amazing postcolonial theorist/cultural critic—she’s someone I read a lot. Specifically, in her text “The Protestant Ethnic & The Spirit of Capitalism,” she talks about how there’s often a pressure on ethnic and sexual minorities—to overdeterminatively disclose just how ‘ethnic’ or ‘minority’ they are—ultimately in a way that is recognisable, and thus legible and consumable, by the majority, or by those in power/with the most cultural buying power. There’s a big hype in the market right now for figurative works, especially from queer artists or artists of colour—its problematic in a few ways as it impels minority artists to produce work that is legibly ‘minority,’ which might end up being stifling creativity and innovation in the long-run. It’s also a reduction and flattening of the artist’s identity into a price-point, which feels just like a bastardisation and capitalisation of identity politics.

So, my intent in producing English-language poems that are obscured, hard-to-read, and unclear is my own way of responding to these ideas about cultural transmission. I can’t read or write Chinese, and so whenever I see Chinese calligraphy, I experience a simultaneous familiarity and alienation—I feel so intimate with the characters, yet their ultimate meaning escapes me. At this point, I don’t try and understand it—rather I try and appreciate it for what it is. I don’t try and get frustrated. Similarly, my hope is that these poem-pictures (and my use of symbols) avoid an easy, thoughtless consumption. They’re largely illegible, yes, but underneath the treatment of the text is actual legible English. They try and emulate a diasporic, estranged relationship to language. My main hope that they solicit care, concern, and time from the viewer—maybe sometimes frustration, sometimes annoyance— but it’s through their opacity and mystery that they’re meant to invite someone in. Not necessarily to offer themselves up for consumption, I suppose, but more of like a shared dinner if that quite makes sense.

How do you feel regarding this search for intercultural dialogue present in your works? Do you feel included at an intercultural level?

I think that, as someone who has two Chinese parents, but was born and raised in England, I’ve always been intimate with intercultural dialogue. My parents run a Chinese restaurant in the suburbs of Liverpool, which is where I would work as a waiter during my adolescence. I was always very conscious that the food that we would serve to the largely white customers was not at all like the food that I would eat at home—so I’m familiar with the ways that immigrants always have to adapt in order to survive, to produce cultural forms (i.e. Sweet and Sour Pork) that are legible and consumable by the dominant population. But of course, I don’t think this is absolutely negative—it’s a process of creolization, as Glissant might put it, an identity-in-relation. And I’m coming from the position of someone who speaks better French than Chinese!

Coming to America, a few years ago now, was a significant experience for me, interculturally-speaking. I was always Chinese-British, yet upon entry into the states became “Asian-American”, even though I’m not an American national. I became really interested in Chinese-American (and Asian-American) history. I think, in learning about how Chinese people have been in America for over a century—that we have a history that is integral to the making of America as we know it today—I guess I became more assertive with my identity, staking my claim in the racial game, so to speak. I also really love hanging out in the Chinatowns of New York. I feel included in the sense that I know the history of my positionality, but of course Asian-Americans are still elided and excluded from a lot of discourse. It has been changing recently, however.

Your artistic narrative is not only about political-social-cultural inclusion, but it is also about sexual identity. There is a strong queer storytelling frame in your works. Could you tell us more?

Sure. So I discussed before where the title “Crane Seeking Comforts” comes from. I like using animals as signifiers of identity—in other works, I’ve used tigers to signify someone whose Chinese zodiac was the tiger. Other times, I’ve used a butterfly to signify someone who has a butterfly tattoo. But like I mentioned before, the birds here are signifiers, or metaphors, for myself.

“Street-bird of New York, aka: bye bye Birdie” is meant to depict roadkill that one often finds in New York—a bird splayed out. But I wanted the bird to be reborn in a somewhat fabulous fashion—so this piece depicts a rebirth, kind of referring to feeling both broken and reborn after an unhealthy relationship. The piece “Taijitu, aka: Cruising” depicts two birds cruising. I depicted the bottom bird with an erect penis; the top bird is sticking its rear out, its asshole (I guess if it’s a bird it would be its cloaca) signified by the prayer beads. I was trying to draw a metaphorical comparison between the ritualistic act of courtship between two birds, and the act of cruising between two men. Then, “Twobird, aka: Copulation” depicts two birds having sex. The cracked iPhone next to them is meant to indicate a kind of grimy, street-level context—but I wanted to make it glorious, almost dignified. The rays that emanate from the bottom bird’s penis is meant to imply ejaculation. It’s all a bit tongue-in-cheek.

In “Sphincter, aka: Two-Pines,” the poem is about my past relationship. The piece “O’, to be a falling man! aka: Crane Seek Comfort” is a poem that pretty explicitly draws the connection between the two birds and a queer narrative.

The first few lines are:

“Two birds… two Fagots mating in the air / crane seeking comforts / Falcon of the inner ass / is Real petered out / is Real cool / is Real dead / True-vada king”

(Extended interview, courtesy of Chiara Bonanni)